|

Dear all,

From now on my blogs will be hosted on Discover Magazine's news aggregator: 80 Beats. I'll be posting a few things a day, so feel free to check back often!

0 Comments

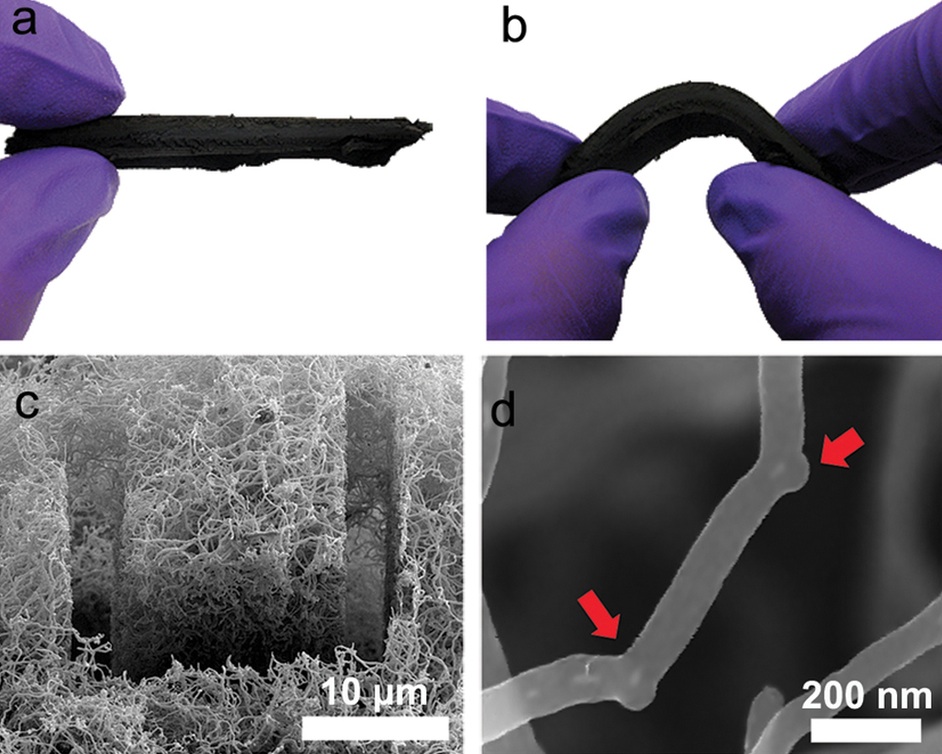

Oil spills are a messy business, but a patent is in the works for a new cleanup solution--the carbon nanotube.

Nanotubes are made out of sheets of carbon, one atom thick, which are rolled into tubes the size of baby carrots. Nanotubes are water repellent, but act as super efficient oil sponges. Each nanotube can absorb up to 100 times its weight in oil. And here’s the kicker: the nanotubes are reusable--you can squeeze or burn the oil out of the sponges without inhibiting their ability to absorb more oil. This offers exciting possibilities for cleaning up oil spills, but thus far the testing has been limited to supercomputer simulations. Some oil spill cleanup methods, like the toxic dispersant used in the BP spill, persist in the environment and cause their own problems. But these tiny sponges are magnetic, which the scientists hope will makes them easier to move and remove from the ocean. While nanotubes have been made for decades, scientists have struggled to control the nanotubes’ growth and dispersal. But scientists at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee have recently added an essential twist. The scientists inserted boron atoms into the mix. Since boron has a different number of valence electrons, it changes the structure of the carbon-based lattice. The boron encouraged more elbow joints to form, creating a 3-dimensional structure, which makes the nanotubes stronger and more flexible...and more efficient at removing oil from ocean waters. The results of the study were published in the journal Nature last week. My family was in town for my graduation this week, and I woke up early to make them eggs for breakfast. I had brought the eggs in a little woven basket from my chicken co-op. Every Tuesday evening I bike to the farm to feed, water and check up on the chickens. In return I get to gather 8 to 12 of their brown/pink/blue/white eggs. It's a little bit of a time commitment. And by time I pay my co-op dues and the feed fees, etc. it ends up being a little pricey.

Well, pricey as compared to the uniformly white dozens offered in styrofoam packaging at King Soopers for $1.29. But significantly less expensive than the fresh eggs I saw advertised at the farmer's market this weekend for $6.50 a dozen. I never know quite how to handle these food decisions. Do I go for the less expensive foodstuffs with unknown origins and shady chemical histories? Or do I opt for the expensive versions that are arguably better for me and the environment? It often become a boxing match between my moral compass and my bank account (which boasts only a dwindling post-graduation student budget). My chicken co-op is one of the few examples of a happy medium that I've been able to find. I know where my eggs come from and that the chickens that lay them are (or at least seem to be) happy. Plus they make the egg-eaters happy too. Dad had his over easy. Mom requested hers scrambled with cheese. But they both agreed that no matter how they're cooked, the eggs from my co-op just taste better. _Last night marked the end of a nine-month era with my colleagues from the Center for Environmental Journalism. It was the fellows' last night in Boulder, and, as such, we had to check a few tasks off our to-do list. Our attempts at getting whiskey milkshakes (or any dessert for that matter) were a fail, but the visit to 1619 Pine Street was anything but. Thanks to the combined navigational skills of Google and Jonathan, we finally got to see the infamous facade, which renewed my appreciation for the city I will call home for a few more months. I have no idea who currently lives at this address near Boulder's main drag, but I am grateful that the residents did not come to the window with a loaded shotgun when I took a flash-heavy picture. (Colorado's recently-passed gun law could have meant that I was a goner). Perhaps the new owners are used to flocks of adoring fans. The old Victorian was home to my favorite television characters, Mork and Mindy. I remember well the joy of Thursday evenings while I was growing up. It was on these nights that my two sisters and I were allowed to stay up half an hour past our bedtime to tune into Nick@Nite for the latest installment of Mork and Mindy. If I was obstinant enough, I could even forego having to change into my pajamas (which were all the way downstairs). Instead I would wriggle into one of my dad's old t-shirts, the short sleeves reaching well below my elbows and the bottom almost brushing the floor.

My sisters and I would scramble up onto Mom and Dad's bed, using our knees and elbows to vie for the limited amount of space between the bed's cliff-like edges. Many bruises and carpet burns were suffered in pursuit of a better view or the privilege of leaning on the brown velour floral-patterned pillow. As soon as Dad had aimed the black plastic remote at the 18-inch television screen, though, our focus was given fully to the alien from the planet Ork. Seeing the house last night brought back the youthful glee evoked by Robin Williams' inherent goofiness. To refresh our Mork and Mindy-related memories (and our palates) my colleagues and I consulted YouTube over a round of margaritas. I remember being enamored by the show when my age was still in the single digits, but I was surprised by how little of the show I actually remembered. The opening credits include shots from downtown Boulder, Boulder Canyon, and Pine Street. Little did I know when my adolescent self was ogling over Mork's egg ship that I would some day be living in the very part of the Earth on which it landed. Today, two decades later, I am proud to call Boulder my second home. Nanu! Nanu! This week marks the end of my master's program at CU Boulder. I have passed all the required courses. I have successfully completed a newspaper internship. I have written and defended my thesis. On Thursday, pending getting all the right signatures on the right lines, I will be walking across the stage in Macky Auditorium wearing a stuffy black cap and gown. (If anyone knows the significance of this apparently academic attire, please enlighten me).

But walking across the stage is not the daunting part. I plan to wear moccasins or Chacos or some such footwear to preclude tripping. The daunting part is the metaphorical parallels of this act--crossing into the next stage of my life, this time with a title and its associated expectations: environmental journalist. I came back to school in search of fulfillment. I had tried the environmental consulting gig. I had given teaching English abroad a shot. But as much as I gained from these experiences, they didn't feel...right. There was no deep sense of satisfaction or purpose. So I dusted off my backpack, sharpened my pencils, and headed up the stairs at 1511 University Ave. to try my hand at graduate school. I chose environmental journalism because it seemed like the one field that could combine the hotdish of disparate interests listed on my undergraduate diploma: environmental studies, English and French. I imagined myself as a foreign correspondent reporting on critical environmental issues in French-speaking Africa. But I quickly found that academia can be just as disenchanting as the "real world." The week I arrived in Boulder, the journalism school closed. None of us knew the implications of this administrative move, and to be honest, two years later, I still don't. Apparently it's nothing to worry about. We operate in a department now instead of a school and I'll still get a pretty, embossed piece of paper that says I win. So as this academic interlude comes to a close, I have begun to reflect on the experience. Did I find graduate school fulfilling? On a strictly academic level, perhaps not. But by being proactive I was able to seek out the elements that made the experience worthwhile. I co-founded an online environmental magazine. I published front page stories in the Daily Camera. I conducted live interviews on KGNU radio. I met amazing people doing amazing work in the field of environmental journalism. In the end, I found reporting on environmental issues to be profoundly satisfying. My stories reached people. Granted, in some cases the audience response was pretty minimal, but it was always exciting to hear that people had read or listened to my work. People reflected and conversed and acted in ways that they otherwise may not have. This felt right. But thus far I have been hired as much-appreciated free labor. The challenge now is to figure out how to make a living out of it, especially since my chosen field (journalism) appears to be on life support. I am leaving grad school with barely a job prospect on the horizon, and this is not for a lack of effort in the application process. Jobs in journalism are becoming fewer, with lower salaries and greater competition. I applied for an entry level reporting job in Seattle a few weeks back and the editor told me that I was one of 600 applicants vying for the position. 600! Another magazine was looking for interns to answer phones, sort mail and fact-check, and they were specifically looking for candidates with master's degrees. This is the type of work I should aspire to after completing two years of graduate school!? I know I shouldn't be picky at this point, but I feel like actually writing is a requisite component. The field of journalism is undergoing an identity crisis right now. And consequently so am I. Hopefully our paths will converge in the form of a job that involves writing and actually pays. In the mean time I will simply write. I have three months until my lease expires, during which time I plan to write--a book, copious amount of grants and job applications, and this blog. I hope you and I will both enjoy the process. For the time being I am redirecting my writing/editing efforts toward The Boulder Stand instead of this blog.

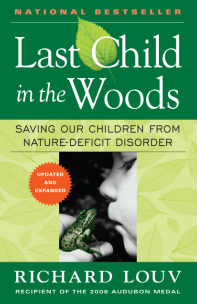

Check it out at theboulderstand.org (please) “We are in more trouble than we think,” said Richard Louv, journalist and bestselling author of Last Child in the Woods, in a public lecture at CU Boulder last Thursday. The most pressing issue in today’s society is not the presidential election, foreign policy, or even the economy. It is the lack of a positive collective environmental attitude, he said. Louv lamented the media’s almost exclusively negative portrayal of the future of the environment. The idea of the far future conjures up images of post-apocalyptic climate change, pollution and urban sprawl, he said. “Everything in the next 40 years must change,” Louv said. For the first time in history, more people now live in urban areas than rural ones, Louv related. Such a shift can lead to one of two future scenarios: People will either encounter the disappearance of daily environmental experiences, or they will initiate the beginning of a whole new kind of city, he said. Louv, ever the optimist, prefers the latter scenario and encourages active reimagination of the urban context. Louv categorizes the general populous into two types: “people who do, and people who write about people who do.” Louv counts himself among the writers rather than the doers. But the popularity and influence of Louv’s writings demonstrates the impact his work has had on environmentalism today. Nearly 500 people - university students, elementary teachers, grandparents, and wilderness advocates among them - filled the seats and lined the walls of the Glen Miller Ballroom to hear him speak. Louv based most of his speech on the book that brought him the fame he now enjoys, Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Since it was first published in 2005, the 390-page manifesto for getting kids outside has been translated into ten different languages and become a national bestseller. The book emphasizes the value of nature for children’s development and education. Louv coined the term “nature deficit disorder” to demonstrate that children today are deprived of crucial interactions with nature. Why such a technical term? “This is an evidence-based society,” Louv said. “We need more evidence.” Or at least today’s society thinks it does. Louv finds such a dependence on data problematic. While teachers and parents have often embrace nature play as a learning tool, school boards tend to exhibit more resistance. We say we want proof, but when we have it--like the correlation between fostering creativity and improved test scores--we don’t act on it, he explained. In 2008 the Audobon Society awarded Louv the prestigious Audobon Medal “for sounding the alarm about the health and societal costs of children's isolation from the natural world—and for sparking a growing movement to remedy the problem.” This award placed him in the environmental leaders’ arena, along with the medal’s previous recipients like Rachel Carson and Jimmy Carter. Officially entering the realm of “people who do,” Louv founded the Children and Nature Network in order to encourage the environmental immersion work his writing promotes. The organization aims to recognize and empower natural leaders, teachers and families. “Together, we can create a world where every child can play, learn and grow in nature,” reads the organization’s homepage. Louv had what he called a “free-range childhood.” He experienced outdoor adventures in his backyard woods, which he described with profound affection, “I owned those woods…I loved those woods. I find something there that I don’t find anywhere else.” But his smile faded when he asked the audience if future generations will have similar opportunities. In an age of stranger danger, he said, helicopter parents and litigation-fearing teachers would rather hover over kids with nature flashcards than let them have an authentic outdoor experience. Education, according to Louv, must nurture wonder and awe as much as knowledge. Louv recently published a follow-up book, The Nature Principle: Human Restoration and the End of Nature-Deficit Disorder, in which he argues that adults, as much as children, are in need of experiencing nature. “I think there is a real hunger...among young people, for an environmentalism that isn’t their parents’ environmentalism,” Louv said. This new environmentalism should be bigger and more inclusive of the multifaceted character of today’s society and should take technology into consideration, he explained. “I’m not anti-tech,” Louv said, which was confirmed by the typing and swiping of his frantic fingers on an iPad and iPhone prior to taking the stage. “I love those things too much.” “The more high-tech our lives become the more nature we need,” he said. Louv suggests that people should embrace the growth of technologies by incorporating them into what he calls a new “hybrid mind,” which combines the best aspects of the virtual and natural worlds. Louv contrasts this approach with the so-called “pup tent” of environmentalism today. Sustainability suggests stasis, while creativity suggests a better future world, he said. This idea of an incredibly hopeful, if currently unfathomable, future is key to Louv’s environmental philosophy. “It’s outrageously unrealistic and that’s the point,” he said. To hear Louv’s optimistic vision of a future world, listen to this poetic excerpt from his talk: Richard Louv has a Dream.

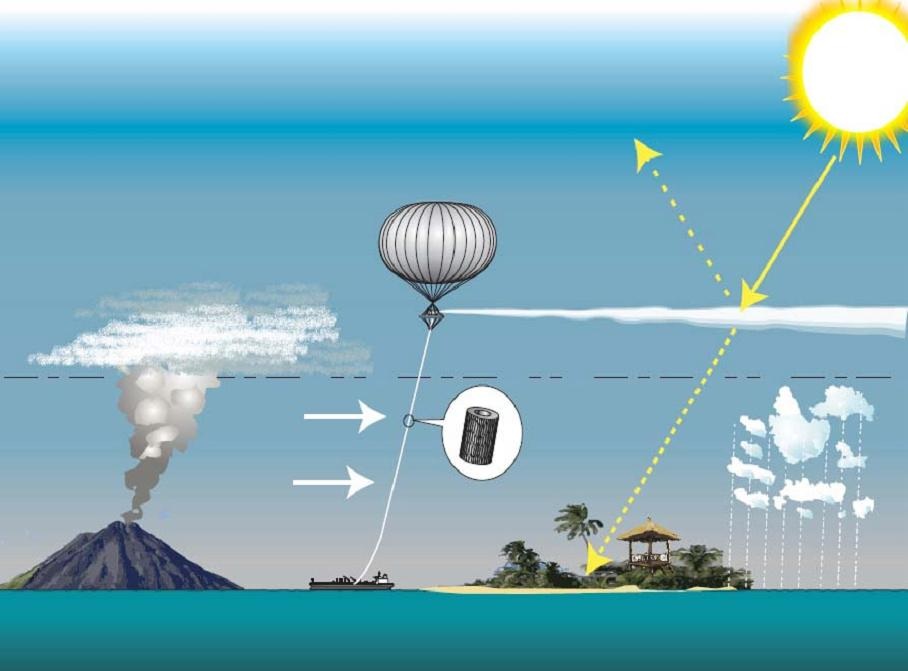

The SPICE project will investigate the feasibility of one so-called geoengineering technique: the idea of simulating natural processes that release small particles into the stratosphere, which then reflect a few percent of incoming solar radiation, with the effect of cooling the Earth with relative speed. Image credit: Hughhunt via Creative Commons license.

Geoengineering rhetoric has made its way into the headlines this week, on both sides of the pond. The Bipartisan Policy Center issued a report on October 4th entitled “Task Force on Climate Remediation Research.” The title itself demonstrates a major shift in the geoengineering conversation with their advised use of the term “climate remediation.” The task force said it avoided the word “geoengineering” in the entire report due to the word’s breadth and imprecision. (Strangely, though, the term geoengineering is included in the report’s subtitle, which appears as a footer of every page of the report. A quick search of the document therefore yields 51 hits for “geoengineering”). Such a euphemistic term, though, met opposition even among the 18 members of the BPC’s task force. The names of three of the report’s authors—David Keith, Granger Morgan, and David G. Victor—were accompanied by the following footnote: “These members support the recommendations of this report, but they do not support the introduction of the new term “climate remediation.” This hearkened back to Roger’s earlier blog regarding the terminology debate surrounding climate deniers/skeptics/inactivists.

The task force’s definition of “climate remediation” provides a much more positive and politically correct spin than some: “intentional actions taken to counter the climate effects of past greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere.” Translation: We screwed up and it’s about time we start thinking about cleaning up the mess. The result was a reluctantly pro-geoengineering report from the BPC. The authors said research is an unfortunate necessity at this point, and emphasized that such practices would not act as a substitute for climate mitigation or adaptation. Yet most mainstream media coverage of the report communicated an air of enthusiasm from the BPC, as was the case with the New York Times, whose headline read, “Group Urges Research Into Aggressive Efforts to Fight Climate Change.” John Vidal, writing for the Guardian’s Environment Blog Thursday, was not particularly supportive of the report’s recommendations, though. His major beef? The agenda-driven affiliations of the task force’s members. He brought up a number of the factors in his blog that we had discussed during our in-class activity regarding the formation of a panel of experts: gender and political party, —“For a start these guys - and they are indeed mostly men - are not bipartisan in any sense that the British would understand”—funding sources, —“The operation is part-funded by big oil, pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies” and vested interests—“the cream of the emerging science and military-led geoengineering lobby with a few neutrals chucked in to give it an air of political sobriety.” Vidal instead applauded the UK’s hesitation when it put off a previously scheduled geoengineering experiment last week. The project boasts a particularly awkward acronym, SPICE, which stands for the Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering project, and is funded by the Engineering & Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), with support from the Science & Technology Facilities Council (STFC). Vidal described the SPICE project in an earlier blog as “a tethered balloon the size of Wembley stadium suspended 20km above Earth, linked to the ground by a giant garden hose pumping hundreds of tonnes of minute chemical particles a day into the thin stratospheric air to reflect sunlight and cool the planet.” Just prior to the project’s intended start date, though, the team announced it would “delay the experiment planned in October, to allow time for more engagement with stakeholders.” So the United Kingdom is putting on the geoengineering brakes while the United States is revving its engine. With the global reach of the problem, though, and the necessity of a comparable scale for proposed solutions, where does that leave the geoengineering/climate remediation conversation? If we can't even agree on the vocabulary, how are we supposed to discuss solutions? Environmental justice is a common theme in climate change discussions. Most often it emerges in the form of fears about the future’s adverse environmental effects disproportionately affecting the poor. As reported by CNN’s Rachel Oliver, “it's the world's poorest who are often put forward as the ones who are likely to feel the affects of climate change the most and are likely to be able to deal with them the least.”

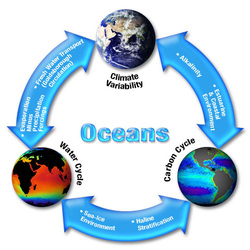

But we don’t need to wait for the tenuous predictions about the long-term effects of climate change to be fulfilled before we see environmental injustice. Today’s world offers plenty of examples. And sea level rise is not the only phenomenon that will displace large numbers of people. Climate mitigation, too, appears to pose a formidable threat. Josh Kron describes one such example in a recent article in the New York Times. In Uganda, a British forestry company has evicted or (to euphemize) otherwise eliminated 20,000 people from their homes to make room for a new tenant on the land: a carbon credit forest that will collect a tidy $1.8 million annually for its carbon sequestration. I find it hard to rationalize such action for the sake of negligible carbon storage. The term “reforestation” boasts an almost universally positive connotation today because it can mitigate countless buzz-word-laden environmental issues, including climate change and biodiversity. But the effects are not so rosy for the people living on the land slated for such purported improvements. Unfortunately the situation in Uganda, which Kron describes as “emblematic of a global scramble for arable land,” is not an isolated occurrence. A Mother Jones article entitled “GM’s Money Trees” described a similar event in Brazil, where “people with some of the world's smallest carbon footprints are being displaced—so their forests can become offsets for SUVs.” The Nature Conservancy partnered with the carbon-emitting corporations to set aside the aforementioned Brazilian forest reserves. In their description of the project, the Nature Conservancy admits that it “isn’t just about climate change — it’s also about preserving one of the last viable remnants of the world’s most endangered tropical forest…[which have been] subjected to deforestation for urban development, farming, and ranching over hundreds of years.” For the sake of the environment, the traditional forest users are portrayed as the bad guys here, not the victims. I see it like this: The metaphorical white picket fences that surround sequestration forest reserves give them an air of good works. But these fences stand between local peoples and the forests on which they, for generations, have relied for survival. And when negative publicity starts to make the fences’ picture-perfect paint peel, forestry companies simply greenwash these fences to regain public support from the international community. I do not doubt the good intentions of The Nature Conservancy’s mission. And climate mitigation is not inherently bad. But what place do people have in the nature that TNC aims to conserve? And when it comes to environmental justice, who should be prioritized—the world’s poor of today or the nebulous future generations of CO2-gushing Americans? Photo courtesy of NASA by Breanna Draxler Global temperatures are set to rise, even though a newly discovered heat sink puts it off for a few years. Scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research released an analysis last Tuesday that determined that deep ocean waters absorb atmospheric heat. This results in a decade-long lag time between rising heat input and rising air temperatures. It’s as though the earth has rented an underwater storage unit for its excess heat. The lease is good for 10 years, after which time the heat will be up for grabs. And the atmosphere is predicted to be the highest bidder. NCAR scientists say the past decade has been an example of this 10-year heat storage lease in action. Greenhouse gases have been on the rise since the turn of the century, and more solar heat is entering the atmosphere than is leaving through radiation. That means there is more heat in the system today, yet global air temperature has increased only minimally. This “missing heat” was unaccounted for until scientists started looking for a deep ocean reservoir for heat. To find that deepwater sink, scientists used Supercomputer simulations of global temperatures to examine the complex climatic interplays of atmosphere, land, oceans and sea ice. From these, they concluded that the “missing” heat is being held in ocean water at depths below 1,000 feet. The scientists predict this lease on underwater heat storage to have a 10-year limit. So while scientists predict more of these short-term plateaus on the graph of global temperatures in the future, overall temperature will continue to rise. |

with intentions.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed