|

“We are in more trouble than we think,” said Richard Louv, journalist and bestselling author of Last Child in the Woods, in a public lecture at CU Boulder last Thursday. The most pressing issue in today’s society is not the presidential election, foreign policy, or even the economy. It is the lack of a positive collective environmental attitude, he said. Louv lamented the media’s almost exclusively negative portrayal of the future of the environment. The idea of the far future conjures up images of post-apocalyptic climate change, pollution and urban sprawl, he said. “Everything in the next 40 years must change,” Louv said. For the first time in history, more people now live in urban areas than rural ones, Louv related. Such a shift can lead to one of two future scenarios: People will either encounter the disappearance of daily environmental experiences, or they will initiate the beginning of a whole new kind of city, he said. Louv, ever the optimist, prefers the latter scenario and encourages active reimagination of the urban context. Louv categorizes the general populous into two types: “people who do, and people who write about people who do.” Louv counts himself among the writers rather than the doers. But the popularity and influence of Louv’s writings demonstrates the impact his work has had on environmentalism today. Nearly 500 people - university students, elementary teachers, grandparents, and wilderness advocates among them - filled the seats and lined the walls of the Glen Miller Ballroom to hear him speak. Louv based most of his speech on the book that brought him the fame he now enjoys, Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Since it was first published in 2005, the 390-page manifesto for getting kids outside has been translated into ten different languages and become a national bestseller. The book emphasizes the value of nature for children’s development and education. Louv coined the term “nature deficit disorder” to demonstrate that children today are deprived of crucial interactions with nature. Why such a technical term? “This is an evidence-based society,” Louv said. “We need more evidence.” Or at least today’s society thinks it does. Louv finds such a dependence on data problematic. While teachers and parents have often embrace nature play as a learning tool, school boards tend to exhibit more resistance. We say we want proof, but when we have it--like the correlation between fostering creativity and improved test scores--we don’t act on it, he explained. In 2008 the Audobon Society awarded Louv the prestigious Audobon Medal “for sounding the alarm about the health and societal costs of children's isolation from the natural world—and for sparking a growing movement to remedy the problem.” This award placed him in the environmental leaders’ arena, along with the medal’s previous recipients like Rachel Carson and Jimmy Carter. Officially entering the realm of “people who do,” Louv founded the Children and Nature Network in order to encourage the environmental immersion work his writing promotes. The organization aims to recognize and empower natural leaders, teachers and families. “Together, we can create a world where every child can play, learn and grow in nature,” reads the organization’s homepage. Louv had what he called a “free-range childhood.” He experienced outdoor adventures in his backyard woods, which he described with profound affection, “I owned those woods…I loved those woods. I find something there that I don’t find anywhere else.” But his smile faded when he asked the audience if future generations will have similar opportunities. In an age of stranger danger, he said, helicopter parents and litigation-fearing teachers would rather hover over kids with nature flashcards than let them have an authentic outdoor experience. Education, according to Louv, must nurture wonder and awe as much as knowledge. Louv recently published a follow-up book, The Nature Principle: Human Restoration and the End of Nature-Deficit Disorder, in which he argues that adults, as much as children, are in need of experiencing nature. “I think there is a real hunger...among young people, for an environmentalism that isn’t their parents’ environmentalism,” Louv said. This new environmentalism should be bigger and more inclusive of the multifaceted character of today’s society and should take technology into consideration, he explained. “I’m not anti-tech,” Louv said, which was confirmed by the typing and swiping of his frantic fingers on an iPad and iPhone prior to taking the stage. “I love those things too much.” “The more high-tech our lives become the more nature we need,” he said. Louv suggests that people should embrace the growth of technologies by incorporating them into what he calls a new “hybrid mind,” which combines the best aspects of the virtual and natural worlds. Louv contrasts this approach with the so-called “pup tent” of environmentalism today. Sustainability suggests stasis, while creativity suggests a better future world, he said. This idea of an incredibly hopeful, if currently unfathomable, future is key to Louv’s environmental philosophy. “It’s outrageously unrealistic and that’s the point,” he said. To hear Louv’s optimistic vision of a future world, listen to this poetic excerpt from his talk: Richard Louv has a Dream.

0 Comments

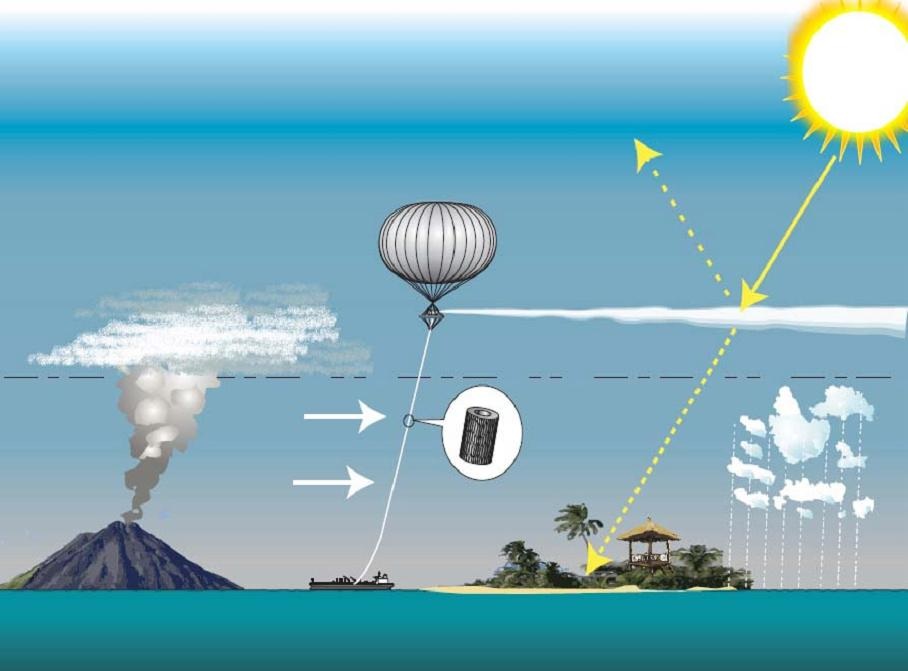

The SPICE project will investigate the feasibility of one so-called geoengineering technique: the idea of simulating natural processes that release small particles into the stratosphere, which then reflect a few percent of incoming solar radiation, with the effect of cooling the Earth with relative speed. Image credit: Hughhunt via Creative Commons license.

Geoengineering rhetoric has made its way into the headlines this week, on both sides of the pond. The Bipartisan Policy Center issued a report on October 4th entitled “Task Force on Climate Remediation Research.” The title itself demonstrates a major shift in the geoengineering conversation with their advised use of the term “climate remediation.” The task force said it avoided the word “geoengineering” in the entire report due to the word’s breadth and imprecision. (Strangely, though, the term geoengineering is included in the report’s subtitle, which appears as a footer of every page of the report. A quick search of the document therefore yields 51 hits for “geoengineering”). Such a euphemistic term, though, met opposition even among the 18 members of the BPC’s task force. The names of three of the report’s authors—David Keith, Granger Morgan, and David G. Victor—were accompanied by the following footnote: “These members support the recommendations of this report, but they do not support the introduction of the new term “climate remediation.” This hearkened back to Roger’s earlier blog regarding the terminology debate surrounding climate deniers/skeptics/inactivists.

The task force’s definition of “climate remediation” provides a much more positive and politically correct spin than some: “intentional actions taken to counter the climate effects of past greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere.” Translation: We screwed up and it’s about time we start thinking about cleaning up the mess. The result was a reluctantly pro-geoengineering report from the BPC. The authors said research is an unfortunate necessity at this point, and emphasized that such practices would not act as a substitute for climate mitigation or adaptation. Yet most mainstream media coverage of the report communicated an air of enthusiasm from the BPC, as was the case with the New York Times, whose headline read, “Group Urges Research Into Aggressive Efforts to Fight Climate Change.” John Vidal, writing for the Guardian’s Environment Blog Thursday, was not particularly supportive of the report’s recommendations, though. His major beef? The agenda-driven affiliations of the task force’s members. He brought up a number of the factors in his blog that we had discussed during our in-class activity regarding the formation of a panel of experts: gender and political party, —“For a start these guys - and they are indeed mostly men - are not bipartisan in any sense that the British would understand”—funding sources, —“The operation is part-funded by big oil, pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies” and vested interests—“the cream of the emerging science and military-led geoengineering lobby with a few neutrals chucked in to give it an air of political sobriety.” Vidal instead applauded the UK’s hesitation when it put off a previously scheduled geoengineering experiment last week. The project boasts a particularly awkward acronym, SPICE, which stands for the Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering project, and is funded by the Engineering & Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), with support from the Science & Technology Facilities Council (STFC). Vidal described the SPICE project in an earlier blog as “a tethered balloon the size of Wembley stadium suspended 20km above Earth, linked to the ground by a giant garden hose pumping hundreds of tonnes of minute chemical particles a day into the thin stratospheric air to reflect sunlight and cool the planet.” Just prior to the project’s intended start date, though, the team announced it would “delay the experiment planned in October, to allow time for more engagement with stakeholders.” So the United Kingdom is putting on the geoengineering brakes while the United States is revving its engine. With the global reach of the problem, though, and the necessity of a comparable scale for proposed solutions, where does that leave the geoengineering/climate remediation conversation? If we can't even agree on the vocabulary, how are we supposed to discuss solutions? Environmental justice is a common theme in climate change discussions. Most often it emerges in the form of fears about the future’s adverse environmental effects disproportionately affecting the poor. As reported by CNN’s Rachel Oliver, “it's the world's poorest who are often put forward as the ones who are likely to feel the affects of climate change the most and are likely to be able to deal with them the least.”

But we don’t need to wait for the tenuous predictions about the long-term effects of climate change to be fulfilled before we see environmental injustice. Today’s world offers plenty of examples. And sea level rise is not the only phenomenon that will displace large numbers of people. Climate mitigation, too, appears to pose a formidable threat. Josh Kron describes one such example in a recent article in the New York Times. In Uganda, a British forestry company has evicted or (to euphemize) otherwise eliminated 20,000 people from their homes to make room for a new tenant on the land: a carbon credit forest that will collect a tidy $1.8 million annually for its carbon sequestration. I find it hard to rationalize such action for the sake of negligible carbon storage. The term “reforestation” boasts an almost universally positive connotation today because it can mitigate countless buzz-word-laden environmental issues, including climate change and biodiversity. But the effects are not so rosy for the people living on the land slated for such purported improvements. Unfortunately the situation in Uganda, which Kron describes as “emblematic of a global scramble for arable land,” is not an isolated occurrence. A Mother Jones article entitled “GM’s Money Trees” described a similar event in Brazil, where “people with some of the world's smallest carbon footprints are being displaced—so their forests can become offsets for SUVs.” The Nature Conservancy partnered with the carbon-emitting corporations to set aside the aforementioned Brazilian forest reserves. In their description of the project, the Nature Conservancy admits that it “isn’t just about climate change — it’s also about preserving one of the last viable remnants of the world’s most endangered tropical forest…[which have been] subjected to deforestation for urban development, farming, and ranching over hundreds of years.” For the sake of the environment, the traditional forest users are portrayed as the bad guys here, not the victims. I see it like this: The metaphorical white picket fences that surround sequestration forest reserves give them an air of good works. But these fences stand between local peoples and the forests on which they, for generations, have relied for survival. And when negative publicity starts to make the fences’ picture-perfect paint peel, forestry companies simply greenwash these fences to regain public support from the international community. I do not doubt the good intentions of The Nature Conservancy’s mission. And climate mitigation is not inherently bad. But what place do people have in the nature that TNC aims to conserve? And when it comes to environmental justice, who should be prioritized—the world’s poor of today or the nebulous future generations of CO2-gushing Americans? |

with intentions.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed