That's a Wrap

by Breanna Draxler, Staff columnist: With Intentions to Inspire

published December 12, 2008

As if the pre-purchased packaging of our modern day commodities isn’t enough, during the holidays we somehow feel the need to add another layer to the excess. One more source of grossly consumptive paper waste—tape it on, rip it off, toss it out. I cringe to think of Dec. 26 and the procession of black plastic trash receptacles that will inevitably line the curb. Body bags stuffed to the gills with the remains of ravaged wrappings.

And to what end? I acknowledge the importance of secrecy when it comes to presents. Gift opening just wouldn’t be the same if all the shaking and guessing weren’t a necessary component. Wrapping paper is, after all, the only thing that lies between a recipient and knowledge of his or her gift. Its appeal, therefore, lies in its ability to deceive and be destroyed. Wrapping paper has no intrinsic value. Why is it, then, that we are willing to spend $4.99 a roll for this stuff?

The colorful Christmas covering may seem harmless, or even friendly, but do not be fooled by its festive façade. Its innocence is as feigned as its necessity. I certainly don’t mean to undermine the element of surprise, but there’s got to be a better, less wasteful way. For that, I propose the Weekly Wrap—a convenient wrapping alternative that can be made out of this very newspaper (after you’ve read it in its entirety of course).

Armed with the power of a glue stick, you too can fight the forces of paper waste. Just follow the simple instructions below to turn your copy of the Weekly into a snazzy holiday gift bag:

1. Glue two sheets of newspaper together.

2. Cut a one-inch strip of paperboard and glue it along the entire top edge of the newspaper.

3. Fold the top edge of the newspaper down over the paperboard, and then fold it over again so that the paperboard is wrapped inside. Glue it down. This will form the reinforced top edge of the bag.

4. Choose a box that is of the size you would like your bag to be. Some particularly convenient box sizes include those of graham crackers, breakfast cereals and the like.

5. Align the top (reinforced) edge of the newspaper with the top edge of the box. The length of the paper should only extend a few inches beyond the length of the box, so you may need to cut a few inches off the bottom of the newspaper.

6. Wrap the newspaper around the box as you would a Christmas present, leaving the top end open. Seal with glue.

7. Reinforce the seams with scotch tape as necessary.

8. Cut a piece of paperboard the same size as the base of the box. Glue it inside the bottom of the bag for structural support.

9. Cut two, ¼-inch strips of paperboard and staple the ends to the bag to form handles.

10. Fill the bag with holiday joy and bequeath it to a deserving recipient.

11. Wash the ink off your hands and repeat.

published December 12, 2008

As if the pre-purchased packaging of our modern day commodities isn’t enough, during the holidays we somehow feel the need to add another layer to the excess. One more source of grossly consumptive paper waste—tape it on, rip it off, toss it out. I cringe to think of Dec. 26 and the procession of black plastic trash receptacles that will inevitably line the curb. Body bags stuffed to the gills with the remains of ravaged wrappings.

And to what end? I acknowledge the importance of secrecy when it comes to presents. Gift opening just wouldn’t be the same if all the shaking and guessing weren’t a necessary component. Wrapping paper is, after all, the only thing that lies between a recipient and knowledge of his or her gift. Its appeal, therefore, lies in its ability to deceive and be destroyed. Wrapping paper has no intrinsic value. Why is it, then, that we are willing to spend $4.99 a roll for this stuff?

The colorful Christmas covering may seem harmless, or even friendly, but do not be fooled by its festive façade. Its innocence is as feigned as its necessity. I certainly don’t mean to undermine the element of surprise, but there’s got to be a better, less wasteful way. For that, I propose the Weekly Wrap—a convenient wrapping alternative that can be made out of this very newspaper (after you’ve read it in its entirety of course).

Armed with the power of a glue stick, you too can fight the forces of paper waste. Just follow the simple instructions below to turn your copy of the Weekly into a snazzy holiday gift bag:

1. Glue two sheets of newspaper together.

2. Cut a one-inch strip of paperboard and glue it along the entire top edge of the newspaper.

3. Fold the top edge of the newspaper down over the paperboard, and then fold it over again so that the paperboard is wrapped inside. Glue it down. This will form the reinforced top edge of the bag.

4. Choose a box that is of the size you would like your bag to be. Some particularly convenient box sizes include those of graham crackers, breakfast cereals and the like.

5. Align the top (reinforced) edge of the newspaper with the top edge of the box. The length of the paper should only extend a few inches beyond the length of the box, so you may need to cut a few inches off the bottom of the newspaper.

6. Wrap the newspaper around the box as you would a Christmas present, leaving the top end open. Seal with glue.

7. Reinforce the seams with scotch tape as necessary.

8. Cut a piece of paperboard the same size as the base of the box. Glue it inside the bottom of the bag for structural support.

9. Cut two, ¼-inch strips of paperboard and staple the ends to the bag to form handles.

10. Fill the bag with holiday joy and bequeath it to a deserving recipient.

11. Wash the ink off your hands and repeat.

The Early Bird Special

by Breanna Draxler, Staff columnist: With Intentions to Inspire

Published November 21, 2008

Environmentalism is a movement—something that denotes forward motion. Like any movement, it requires both support and action. The thing that sets environmentalism apart from other causes, though, is its temporal urgency. You can’t wait for the bandwagon to roll into town before you hop on. By the time environmental issues become mainstream—or are even acknowledged as legitimate issues—it’s usually too late. A belated reaction usually means one of two things: A) the opportunity for action is missed due to a prolonged period of indecision, or B) the situation becomes so dire that little can be done.

The installation of wind turbines on the Gustavus campus is a painful example of the first-case scenario. What wind turbines, you may ask? That’s exactly my point. Gustavus began contemplating the installation of wind turbines in the 90s—when acid wash jeans and Ace of Base were still in style. At that point in time, according to Professor of Physics Chuch Niederriter, a member of the seven-person Gustavus Wind Energy Group, the idea of wind power was still relatively new, and support was minimal. Over the next several years, though, students, staff, faculty and administrators became actively involved in the issue—monitoring wind speeds, researching technologies and conducting sophisticated cost-benefit analyses.

According to Jim Dontje, the director of Gustavus’ Johnson Center for Environmental Innovation, and another member of the Wind Energy Group, they determined two turbines with capactities of 2 to 2.5 megawatts each would generate enough energy to supply an estimated 60 to 70 percent of the college’s total electricity consumption. In addition, he estimates that we would also be eliminating Gustavus’ greenhouse gas emissions by 40 to 50 percent. It’s hard to deny the obvious benefits of such a project. As 2001 came to a close, says Niederriter, “everyone was on board.”

It wasn’t until late 2006, though, that the project got the official go-ahead, and by that point it was too late. Wind turbines were (and still are) a hot commodity in high demand. For reasons of cost-effectiveness, most companies will no longer consider orders of any less than 50 turbines. Our measly two can’t even get us on the waiting list. Despite the continued efforts of dedicated Gusties and their loyal allies—the commerce department, wind lobbying groups and fellow Midwestern colleges—our attempts have proven futile.

The disheartening disconnect: we supported the project in theory but missed the window of opportunity in which to act on it. Why the delay? Aside from some minor consulting setbacks, we were simply afraid of taking a risk and making an investment. I’ll admit that the initial cost was a little daunting: around $3.5 million upfront, plus $40,000 a year for maintenance. But between an annual savings of about $1 million (two-thirds of our electricity budget) and the profit from selling excess wind back to the grid, the Wind Energy Group estimated that the payback would have taken a mere seven to ten years. If we had followed through with the project in 2001, when the support and supply were simultaneously present, the turbines could already have been installed and paid off. Now, though, there is little hope that Gustavus will have turbines anytime in the near future.

This issue isn’t just a matter of money, though. It’s a matter of being proactive about our priorities and investing in ideas we believe in. Yes, this means taking risks. Yes, this means making changes. But that’s what we at Gustavus are all about, right?

That’s what the college’s new Commission Gustavus 150 claims. According to the online press release, available from Gustavus’ homepage, the commission has been established on this campus with the purpose of “integrating and expanding the College’s Strategic Plan and making recommendations for the College’s future advancement.” Gustavus is looking for change. Eight task forces have been created to examine key issues, and their topics are as follows:

1. Academic Affairs and New Initiatives

2. Interdisciplinary Programs

3. Student Life

4. Community Engagement

5. Global and Multicultural issues

6. Faith

7. Stewardship

8. Facilities and Finances

The list appears pretty exhaustive, but where does environmentalism fit in? I suppose we might be able to squeeze a few project in the “new initiatives” category, or argue them as “community engagement” endeavors, but this misses the point.

Even if environmental practices are mentioned in some footnote of Commission Gustavus 150’s text, the fundamental issue lies in its omission from the aforementioned list. Environmental issues are critical to the future of our institution and should therefore be an explicit priority.

If those higher-up don’t think this cause warrants a task force, then we, as members of the Gustavus community, need to take on that role. Commission Gustavus 150 has opened the door for change, and we need to hop on the bandwagon and parade it around Ring Road before it is too late. Our priorities can and should impact the college’s Strategic Plan. Take a risk. Take action. Make it known how we want Gustavus to look for its 150th birthday—greener and more sustainable than ever.

Published November 21, 2008

Environmentalism is a movement—something that denotes forward motion. Like any movement, it requires both support and action. The thing that sets environmentalism apart from other causes, though, is its temporal urgency. You can’t wait for the bandwagon to roll into town before you hop on. By the time environmental issues become mainstream—or are even acknowledged as legitimate issues—it’s usually too late. A belated reaction usually means one of two things: A) the opportunity for action is missed due to a prolonged period of indecision, or B) the situation becomes so dire that little can be done.

The installation of wind turbines on the Gustavus campus is a painful example of the first-case scenario. What wind turbines, you may ask? That’s exactly my point. Gustavus began contemplating the installation of wind turbines in the 90s—when acid wash jeans and Ace of Base were still in style. At that point in time, according to Professor of Physics Chuch Niederriter, a member of the seven-person Gustavus Wind Energy Group, the idea of wind power was still relatively new, and support was minimal. Over the next several years, though, students, staff, faculty and administrators became actively involved in the issue—monitoring wind speeds, researching technologies and conducting sophisticated cost-benefit analyses.

According to Jim Dontje, the director of Gustavus’ Johnson Center for Environmental Innovation, and another member of the Wind Energy Group, they determined two turbines with capactities of 2 to 2.5 megawatts each would generate enough energy to supply an estimated 60 to 70 percent of the college’s total electricity consumption. In addition, he estimates that we would also be eliminating Gustavus’ greenhouse gas emissions by 40 to 50 percent. It’s hard to deny the obvious benefits of such a project. As 2001 came to a close, says Niederriter, “everyone was on board.”

It wasn’t until late 2006, though, that the project got the official go-ahead, and by that point it was too late. Wind turbines were (and still are) a hot commodity in high demand. For reasons of cost-effectiveness, most companies will no longer consider orders of any less than 50 turbines. Our measly two can’t even get us on the waiting list. Despite the continued efforts of dedicated Gusties and their loyal allies—the commerce department, wind lobbying groups and fellow Midwestern colleges—our attempts have proven futile.

The disheartening disconnect: we supported the project in theory but missed the window of opportunity in which to act on it. Why the delay? Aside from some minor consulting setbacks, we were simply afraid of taking a risk and making an investment. I’ll admit that the initial cost was a little daunting: around $3.5 million upfront, plus $40,000 a year for maintenance. But between an annual savings of about $1 million (two-thirds of our electricity budget) and the profit from selling excess wind back to the grid, the Wind Energy Group estimated that the payback would have taken a mere seven to ten years. If we had followed through with the project in 2001, when the support and supply were simultaneously present, the turbines could already have been installed and paid off. Now, though, there is little hope that Gustavus will have turbines anytime in the near future.

This issue isn’t just a matter of money, though. It’s a matter of being proactive about our priorities and investing in ideas we believe in. Yes, this means taking risks. Yes, this means making changes. But that’s what we at Gustavus are all about, right?

That’s what the college’s new Commission Gustavus 150 claims. According to the online press release, available from Gustavus’ homepage, the commission has been established on this campus with the purpose of “integrating and expanding the College’s Strategic Plan and making recommendations for the College’s future advancement.” Gustavus is looking for change. Eight task forces have been created to examine key issues, and their topics are as follows:

1. Academic Affairs and New Initiatives

2. Interdisciplinary Programs

3. Student Life

4. Community Engagement

5. Global and Multicultural issues

6. Faith

7. Stewardship

8. Facilities and Finances

The list appears pretty exhaustive, but where does environmentalism fit in? I suppose we might be able to squeeze a few project in the “new initiatives” category, or argue them as “community engagement” endeavors, but this misses the point.

Even if environmental practices are mentioned in some footnote of Commission Gustavus 150’s text, the fundamental issue lies in its omission from the aforementioned list. Environmental issues are critical to the future of our institution and should therefore be an explicit priority.

If those higher-up don’t think this cause warrants a task force, then we, as members of the Gustavus community, need to take on that role. Commission Gustavus 150 has opened the door for change, and we need to hop on the bandwagon and parade it around Ring Road before it is too late. Our priorities can and should impact the college’s Strategic Plan. Take a risk. Take action. Make it known how we want Gustavus to look for its 150th birthday—greener and more sustainable than ever.

The Bipedal Revolution

by Breanna Draxler, Staff columnist: With Intentions to Inspire

published November 7, 2008

I am by no means a die-hard biker. I rarely sport a helmet for fear of flattening the ‘do and I haven’t been seen wearing spandex shorts in public since 1994. I’ll admit that I’m even a little afraid of those cool shoe clip things that hook into the pedals. My balance is questionable enough as it is without the added pressure of having my limbs firmly affixed to the motion-makers.

But since the first time I mounted the aerodynamic aluminum frame of a bicycle, I’ve learned that you don’t have to be a fanatic to enjoy the sport. Put me on my trusty Trek and I will ride for hours—getting groceries, working out or simply joy riding. Whether the setting is urban or rural, a bike always fits.

The environmental perks are also a plus; my lime-colored cycle is green in more ways in one. The only tank that requires filling on this bipedal vehicle is the tires (and despite rising costs during tour current economic crisis, the price of air has remained relatively stable). No fossil fuels go in and no pollution comes out. It’s a win-win situation in environmental terms, so why don’t more people travel by trike?

Perhaps it’s a matter of efficiency. I mean, it takes a lot of energy to ride a bike, right? On the other hand, according to bikewebsite.com, a person on a bicycle is the most efficient means of transportation on earth. In terms of energy expended to transport weight over distance, there is no animal or machine on earth that can beat the efficiency of a biker. That’s pretty darn efficient if you ask me.

Plus, there’s a certain feeling of accomplishment knowing that you produced and expended the energy necessary to go from one place to another. Self-sufficiency begets many a warm fuzzy feeling, not to mention the physical benefits of two-wheeled travel. Exercise and endorphins are a tough combo to beat, especially considering the alternative of traffic jams and uncomfortable upholstery. Burning calories or burning gas? You make the call.

The bicycle is definitely my vehicle of choice, especially for my daily commute during the summer months. It makes the ride home something to look forward to, rather than a simple transition period between home and work and back again. Cruising down County Road F with the wind in my hair and the sun on my face is enough to induce some serious bliss.

But the positive effects of bicycle transportation go far beyond my mood. In fact, I’m going to go ahead and say that biking can ameliorate the effects of pretty much every major crisis our world faces today: global warming, dependence on foreign oil, obesity, nature deficit disorder, you name it. This seems like a pretty convincing list of reasons. I think it’s time to make a serious shift in the type of vehicles that dominate our transportation sector.

St. Helen’s School in Newbury, Ohio seems to be on the right track. Here, in addition to reading, writing and ‘rithmetic, the students are required to take unicycling classes. They even go so far as to cycle in the hallways between classes. If they can pull it off without too many collisions, I don’t see why sleepy little St. Peter can’t follow suit. And heck, why stop there?

Let’s bring cycling to the global level. With my bike by my side—as sidekick, steed and secret weapon alike—I seek to change the world. My fellow Gusties, this is a call to arms…or legs as the case may be. Whip out your Huffy and join in the bipedal revolution!

published November 7, 2008

I am by no means a die-hard biker. I rarely sport a helmet for fear of flattening the ‘do and I haven’t been seen wearing spandex shorts in public since 1994. I’ll admit that I’m even a little afraid of those cool shoe clip things that hook into the pedals. My balance is questionable enough as it is without the added pressure of having my limbs firmly affixed to the motion-makers.

But since the first time I mounted the aerodynamic aluminum frame of a bicycle, I’ve learned that you don’t have to be a fanatic to enjoy the sport. Put me on my trusty Trek and I will ride for hours—getting groceries, working out or simply joy riding. Whether the setting is urban or rural, a bike always fits.

The environmental perks are also a plus; my lime-colored cycle is green in more ways in one. The only tank that requires filling on this bipedal vehicle is the tires (and despite rising costs during tour current economic crisis, the price of air has remained relatively stable). No fossil fuels go in and no pollution comes out. It’s a win-win situation in environmental terms, so why don’t more people travel by trike?

Perhaps it’s a matter of efficiency. I mean, it takes a lot of energy to ride a bike, right? On the other hand, according to bikewebsite.com, a person on a bicycle is the most efficient means of transportation on earth. In terms of energy expended to transport weight over distance, there is no animal or machine on earth that can beat the efficiency of a biker. That’s pretty darn efficient if you ask me.

Plus, there’s a certain feeling of accomplishment knowing that you produced and expended the energy necessary to go from one place to another. Self-sufficiency begets many a warm fuzzy feeling, not to mention the physical benefits of two-wheeled travel. Exercise and endorphins are a tough combo to beat, especially considering the alternative of traffic jams and uncomfortable upholstery. Burning calories or burning gas? You make the call.

The bicycle is definitely my vehicle of choice, especially for my daily commute during the summer months. It makes the ride home something to look forward to, rather than a simple transition period between home and work and back again. Cruising down County Road F with the wind in my hair and the sun on my face is enough to induce some serious bliss.

But the positive effects of bicycle transportation go far beyond my mood. In fact, I’m going to go ahead and say that biking can ameliorate the effects of pretty much every major crisis our world faces today: global warming, dependence on foreign oil, obesity, nature deficit disorder, you name it. This seems like a pretty convincing list of reasons. I think it’s time to make a serious shift in the type of vehicles that dominate our transportation sector.

St. Helen’s School in Newbury, Ohio seems to be on the right track. Here, in addition to reading, writing and ‘rithmetic, the students are required to take unicycling classes. They even go so far as to cycle in the hallways between classes. If they can pull it off without too many collisions, I don’t see why sleepy little St. Peter can’t follow suit. And heck, why stop there?

Let’s bring cycling to the global level. With my bike by my side—as sidekick, steed and secret weapon alike—I seek to change the world. My fellow Gusties, this is a call to arms…or legs as the case may be. Whip out your Huffy and join in the bipedal revolution!

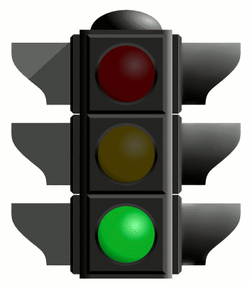

Green Doesn't Always Mean Go

by Breanna Draxler, Staff Columnist: With Intentions to Inspire

published October 3, 2008

I own too much stuff. Too many clothes. Too many books. Too much useless crap. I am aware of this unwilling obsession, but I still find myself clinging to that hideous blue velvet blazer that somehow found its way into my laundry. I have never worn it. I never will wear it. But there’s always that little voice in the back of my closet telling me that someday that blazer might be just the thing. Despite this materialistic tendency, I would not consider myself a packrat. I am what you would call an American.

I find it ironic that we, as Americans, think we can save the earth by spending money. We buy more fuel-efficient cars and eco-friendly products, thinking that these purchases will improve the condition of our planet. The negative environmental effects of these products may be less than their non-green counterparts, but they are still produced and marketed in order to make a profit. Our collective environmental ethics are not going to be changed at the corporate level. We, the consumers, have the purchasing power and we must use it wisely.

Green products provide “solutions” that ease our environmental consciences without cramping our stuff-obsessed styles. They have become a fad in our mainstream, materialistic culture. Like everything else on the shelves, though, these products become obsolete as soon as a slightly better technology comes along. We get so caught up in this succession of false panaceas that our attention is diverted from any real attempts to make lasting change.

Green-themed T-shirts, for example, are amusingly futile. They promote environmentally-minded principles, but actually fail to practice them. They send messages in attempts to change the world, but what messages do they really convey? The “Hug a Tree” slogan scrawled across the front is explicit in its intentions, but has much less of an impact on our environment than the “Made in Malaysia” printed discreetly on its tag.

By buying ever-greener products, we are simply buying time. It is not going to change our consumer-driven culture or have any sort of meaningful impact on our environment. Buying, in any capacity, is not the solution to the problem of over-consumption.

What is it about buying things that is so alluring anyway?

Perhaps it’s the ability to glance at a price-tag with practices nonchalance and vanquish this numerical foe with one graceful swipe of a credit card. Or maybe it’s a monetary means of making a bad day better. I know when I’m feeling down, a new pair of over-priced shoes will do the trick (note sarcasm). Or perhaps it’s the satisfaction derived from ripping off the excessive amount of plastic packaging and touching…holding…possessing something new.

William McDonough and Michael Baungart, authors of the paperless book entitled Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, call this act a “metaphorical defloration.” I find this parallel disturbing in its accuracy. We buy a product, insisting that its materials be virgin. We enjoy it until the newness fades and a better/faster/newer version is available. A version that we absolutely have to have.

I know that it is hopelessly idealistic to think that we can eliminate unnecessary spending entirely, but it is not out-of-the-picture to be more intentional about it. Your choices at the checkout make a statement, so make it a good one. Tell the world that you care about the environment enough to change your buying habits. Distinguish between wants and needs. Go for used instead of new, despite the stigmas.

You opt for the used textbooks, right, so what’s wrong with used clothing? Or dishes? Or appliances? They cost less, and last I checked that was a good thing. For some reason, though, we automatically assume that the cheapness is indicative of quality as well as price. This is not the case. The cooties epidemic of ’98 is long since past, so it’s about time we get over our fear of the used.

In some cases, being pre-owned is actually desirable. It seems silly to me, though, that this distinction is not applied universally. Why does the value of an item increase if its previous owner was Joe Mauer, but the opposite is true if it was formerly possessed by Average Joe? A Joe is a Joe is a Joe. This is a simply concept, or rather, a concept of simplicity. You do not spend in order to save; you save in order to save.

published October 3, 2008

I own too much stuff. Too many clothes. Too many books. Too much useless crap. I am aware of this unwilling obsession, but I still find myself clinging to that hideous blue velvet blazer that somehow found its way into my laundry. I have never worn it. I never will wear it. But there’s always that little voice in the back of my closet telling me that someday that blazer might be just the thing. Despite this materialistic tendency, I would not consider myself a packrat. I am what you would call an American.

I find it ironic that we, as Americans, think we can save the earth by spending money. We buy more fuel-efficient cars and eco-friendly products, thinking that these purchases will improve the condition of our planet. The negative environmental effects of these products may be less than their non-green counterparts, but they are still produced and marketed in order to make a profit. Our collective environmental ethics are not going to be changed at the corporate level. We, the consumers, have the purchasing power and we must use it wisely.

Green products provide “solutions” that ease our environmental consciences without cramping our stuff-obsessed styles. They have become a fad in our mainstream, materialistic culture. Like everything else on the shelves, though, these products become obsolete as soon as a slightly better technology comes along. We get so caught up in this succession of false panaceas that our attention is diverted from any real attempts to make lasting change.

Green-themed T-shirts, for example, are amusingly futile. They promote environmentally-minded principles, but actually fail to practice them. They send messages in attempts to change the world, but what messages do they really convey? The “Hug a Tree” slogan scrawled across the front is explicit in its intentions, but has much less of an impact on our environment than the “Made in Malaysia” printed discreetly on its tag.

By buying ever-greener products, we are simply buying time. It is not going to change our consumer-driven culture or have any sort of meaningful impact on our environment. Buying, in any capacity, is not the solution to the problem of over-consumption.

What is it about buying things that is so alluring anyway?

Perhaps it’s the ability to glance at a price-tag with practices nonchalance and vanquish this numerical foe with one graceful swipe of a credit card. Or maybe it’s a monetary means of making a bad day better. I know when I’m feeling down, a new pair of over-priced shoes will do the trick (note sarcasm). Or perhaps it’s the satisfaction derived from ripping off the excessive amount of plastic packaging and touching…holding…possessing something new.

William McDonough and Michael Baungart, authors of the paperless book entitled Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, call this act a “metaphorical defloration.” I find this parallel disturbing in its accuracy. We buy a product, insisting that its materials be virgin. We enjoy it until the newness fades and a better/faster/newer version is available. A version that we absolutely have to have.

I know that it is hopelessly idealistic to think that we can eliminate unnecessary spending entirely, but it is not out-of-the-picture to be more intentional about it. Your choices at the checkout make a statement, so make it a good one. Tell the world that you care about the environment enough to change your buying habits. Distinguish between wants and needs. Go for used instead of new, despite the stigmas.

You opt for the used textbooks, right, so what’s wrong with used clothing? Or dishes? Or appliances? They cost less, and last I checked that was a good thing. For some reason, though, we automatically assume that the cheapness is indicative of quality as well as price. This is not the case. The cooties epidemic of ’98 is long since past, so it’s about time we get over our fear of the used.

In some cases, being pre-owned is actually desirable. It seems silly to me, though, that this distinction is not applied universally. Why does the value of an item increase if its previous owner was Joe Mauer, but the opposite is true if it was formerly possessed by Average Joe? A Joe is a Joe is a Joe. This is a simply concept, or rather, a concept of simplicity. You do not spend in order to save; you save in order to save.

Cleansing Your Environmental Palate

by Breanna Draxler, Staff columnist: With Intentions to Inspire

published September 19, 2008

The senior class edition of The Echo (a highly censored but enjoyably lame periodical put out by the students of Amery High School) made the following prediction for my post-graduation future: In five years, Breanna Draxler will be a vegetarian living in a cabin in the woods.

As a girl who grew up in a tent in the front yard, relocating to a cabin in the woods would hardly be a stretch. Giving up meat, though? Not happening. Animal rights do not concern me, and, quite frankly, I like the taste of meat too much. Why is it, then, that four years later it is only the first half of this post-secondary prophesy that has been fulfilled?

I have come to see beyond the stigmas associated with vegetarianism. For me, it isn’t about saving swine from the slaughterhouse. It’s a simply matter of environmental efficiency.

Meat production is one of the most resource-consuming and polluting industries in the world. Livestock-related water consumption and pollution disturb the vast majority of freshwater bodies in the United States. Tropical rainforests are being destroyed at a frightening rate to raise and graze livestock. Brazil drafted a plan for emergency action to save their rainforests earlier this year, after a government report declared that nearly 1,250 square miles had been cleared in a period of only five months.

Exorbitant amounts of energy and fossil fuels go into the meat industry, and even more pollution comes out. The greenhouse gases attributed to meat production alone account for a whopping one fifth of the world’s total emissions—more than the entire transportation sector, based on estimates from the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization.

A recent study from Japan’s National Institute of Livestock and Grassland Science found that the production of a single pound of meat emits as much carbon dioxide as a 70-mile drive in the average European car. That means that the 16-ounce steak you ordered at Famous Dave’s actually creates more pollution than your drive to Bloomington to get it!

Add to that track record the incessant amount of excrement and methane that each animal creates, and you’ve got yourself a recipe for environmental disaster…also known as our current state of meat-obsessed affairs. The worst part is that meat consumption is growing with no signs of stopping. The obvious solution would be to reduce meat production, but would eating less meat really make a difference?

I argue it would. According to an article by David and Marcia Pimentel, published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, the amount of grain we currently dedicate to livestock feed alone would be enough to feed 840 million people on vegetarian diets—almost three times the current population of the United States. By eating the grains directly, we avoid the unnecessary steps that make food production such an inefficient and energy-intensive process.

This is where environmental vegetarianism comes in. By reducing or replacing meat in your diet, you can significantly reduce the impact of your nutritional regime on this lovely planet of ours. Order your pizza without the pepperoni next time, or opt for the meatless spaghetti sauce. This doesn’t have to be difficult.

The problem is that justifying a dietary shift towards vegetarianism inevitably—and unintentionally—puts an omnivorous audience in the wrong. To clarify: meat, in itself, is not a bad thing. Nor am I recommending that everyone swap their steaks for soy burgers. (Most imitation meat products still make me nauseous).

The goal is to encourage an environmental consciousness that speaks louder than the growls of one’s meat-loving stomach. Being realistic is as important as being conscientious. Our current pro-meat eating habits are just that: habits. We eat meat because it is available and because we are accustomed to it.

All you need to do is be more intentional about what you put on your lunch tray or in your shopping cart. Seek out free-range chicken and grass-fed beef, whose rearing methods are far more sustainable than those on feedlots. You can also cut down on transportation costs by buying them from local retailers. Pigs and chickens convert grain into meat more efficiently than cows, so try to go for white meat. If you’re feeling really ambitious, dust off that hunting license and procure yourself a bit of venison.

There are few actions that affect the environment as directly and as immediately as our food choices, so make good ones. You—and the planet—will be better off for it.

published September 19, 2008

The senior class edition of The Echo (a highly censored but enjoyably lame periodical put out by the students of Amery High School) made the following prediction for my post-graduation future: In five years, Breanna Draxler will be a vegetarian living in a cabin in the woods.

As a girl who grew up in a tent in the front yard, relocating to a cabin in the woods would hardly be a stretch. Giving up meat, though? Not happening. Animal rights do not concern me, and, quite frankly, I like the taste of meat too much. Why is it, then, that four years later it is only the first half of this post-secondary prophesy that has been fulfilled?

I have come to see beyond the stigmas associated with vegetarianism. For me, it isn’t about saving swine from the slaughterhouse. It’s a simply matter of environmental efficiency.

Meat production is one of the most resource-consuming and polluting industries in the world. Livestock-related water consumption and pollution disturb the vast majority of freshwater bodies in the United States. Tropical rainforests are being destroyed at a frightening rate to raise and graze livestock. Brazil drafted a plan for emergency action to save their rainforests earlier this year, after a government report declared that nearly 1,250 square miles had been cleared in a period of only five months.

Exorbitant amounts of energy and fossil fuels go into the meat industry, and even more pollution comes out. The greenhouse gases attributed to meat production alone account for a whopping one fifth of the world’s total emissions—more than the entire transportation sector, based on estimates from the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization.

A recent study from Japan’s National Institute of Livestock and Grassland Science found that the production of a single pound of meat emits as much carbon dioxide as a 70-mile drive in the average European car. That means that the 16-ounce steak you ordered at Famous Dave’s actually creates more pollution than your drive to Bloomington to get it!

Add to that track record the incessant amount of excrement and methane that each animal creates, and you’ve got yourself a recipe for environmental disaster…also known as our current state of meat-obsessed affairs. The worst part is that meat consumption is growing with no signs of stopping. The obvious solution would be to reduce meat production, but would eating less meat really make a difference?

I argue it would. According to an article by David and Marcia Pimentel, published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, the amount of grain we currently dedicate to livestock feed alone would be enough to feed 840 million people on vegetarian diets—almost three times the current population of the United States. By eating the grains directly, we avoid the unnecessary steps that make food production such an inefficient and energy-intensive process.

This is where environmental vegetarianism comes in. By reducing or replacing meat in your diet, you can significantly reduce the impact of your nutritional regime on this lovely planet of ours. Order your pizza without the pepperoni next time, or opt for the meatless spaghetti sauce. This doesn’t have to be difficult.

The problem is that justifying a dietary shift towards vegetarianism inevitably—and unintentionally—puts an omnivorous audience in the wrong. To clarify: meat, in itself, is not a bad thing. Nor am I recommending that everyone swap their steaks for soy burgers. (Most imitation meat products still make me nauseous).

The goal is to encourage an environmental consciousness that speaks louder than the growls of one’s meat-loving stomach. Being realistic is as important as being conscientious. Our current pro-meat eating habits are just that: habits. We eat meat because it is available and because we are accustomed to it.

All you need to do is be more intentional about what you put on your lunch tray or in your shopping cart. Seek out free-range chicken and grass-fed beef, whose rearing methods are far more sustainable than those on feedlots. You can also cut down on transportation costs by buying them from local retailers. Pigs and chickens convert grain into meat more efficiently than cows, so try to go for white meat. If you’re feeling really ambitious, dust off that hunting license and procure yourself a bit of venison.

There are few actions that affect the environment as directly and as immediately as our food choices, so make good ones. You—and the planet—will be better off for it.